Steven E. Runge, High

Definition Commentary: Romans

(Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2014), 23–34.

Romans 1:18–32

If we can’t be won over by kindness, perhaps the fear of God will get our attention. This is not a scare tactic but an imminent reality, a natural consequence of our sin. What is there to fear? The counterpart to the revelation of God’s righteousness: the revelation of His wrath.

Important Revelation: Verses 17–18 reveal two things, one positive, one negative. The negative—the wrath of God—is provoked by humanity’s negative response to the revelation of God’s righteousness.

Pay attention to where the wrath is focused. It’s not revealed against people—even though we are the cause—but against all our ungodliness and wickedness. Paul uses a series of closely related support clauses to illustrate a vivid picture of the folks under judgment. Each supporting clause begins a digression that steps further and further off the main line of his argument, just like we would do in English using a series of rhetorical questions.

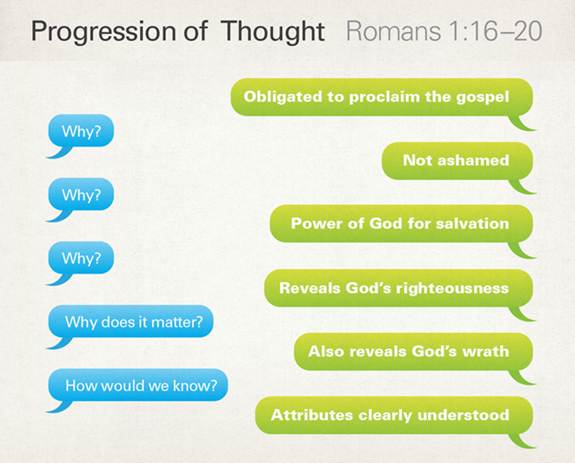

Progression of Thought: Paul uses a series of closely related statements to accomplish the same kind of supporting development he would have achieved by using rhetorical questions to connect thoughts. Each statement supports what precedes. Each steps further off the preceding line of argument and onto a digression. An extended digression begins in 1:20–21 and continues through the end of Romans 4.

Each of these ideas bears a close relation to the one that immediately precedes, but they represent a pretty big leap when we compare where Paul begins (his obligation to preach) with where he ends (God making His attributes clearly understood). In other words, support A links to B and then to C, D, and E, but A seems to bear little connection to E. This flow of thought fosters a sense that each piece naturally derives from the one before it. It also allows Paul to move in a different direction subtly, without making one dramatic move. It creates powerful connections that might have seemed more abrupt had he used a more direct approach.

So why is God’s wrath revealed? What is the source of humanity’s ungodliness? They have rejected the created order of things that God set in place from the beginning. This rejection doesn’t just affect humankind; rejecting God’s created order affects God and upsets how He intended things to be. He didn’t create things for our good pleasure, but for His. Paul characterizes this rejection as three different exchanges:

1. the glory of the immortal God for the likeness of mortal beings

2. the truth of God for a lie

3. natural sexual relations for what is unnatural

Although these are three separate rejections, they all represent an overturning of God’s intended order. Thus, the message of Romans is not simply about the forgiveness of sin and reconciliation with God. Rather, Paul describes a problem confronting all of creation, not just humankind. In Romans 8:22, Paul specifically refers to creation groaning in agony as it awaits the same needed restoration we do. So as you read through the balance of this section, remember that Paul has much more in mind than the universal problem of sin. And as we will see in 2:1, Paul has all people in view here and not just Gentile idolaters.

The people facing God’s impending judgment are those who have perpetrated the disorder. Paul describes them less than objectively in 1:18 as suppressors of God’s truth. How have they suppressed it? Verse 19 states that they have missed what God has made clear about Himself. How is it their fault? Well, God has clearly revealed everything that is knowable about Him. Like what? Verse 20 outlines the attributes He used to reveal Himself, with the result being that these perpetrators are without excuse.

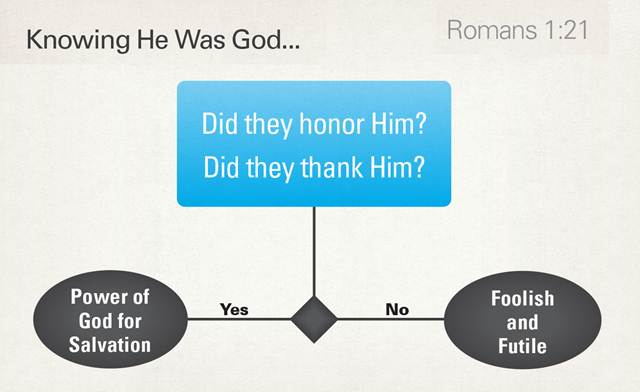

Paul often relates his points to one another as though they are natural consequences of a decision. If you decide on choice A, then you will receive consequence B. Different choices may bring about different results, but Paul typically correlates consequences with a decision. In 1:21, Paul uses a rhetorical question to elicit a pair of contrasting paths. He makes clear that refusing to honor God brings about a negative result, and elicits the possibility that the choice to honor Him would have led to a different outcome.

Since in 1:20 Paul tells us that God has clearly made Himself known by revealing His divine attributes, we cannot blame our separation from God on our lack of knowledge. Rather, the problem stems from our response to the knowledge He gives. Verse 21 is pivotal for understanding this problem. Paul makes clear in 1:21 that although the people knew God, they chose not to honor Him as God and thus rejected His intended order. It’s not as if they misunderstood who He was; in fact, it was quite the opposite. They understood exactly who He was, but refused to honor Him as God (1:21). This initial rejection leads to even worse natural consequences: futile thinking and a darkening of their hearts (1:21).

Paul’s line of reasoning eliminates any possible excuses people might make by highlighting the intentionality behind their rejection of His order. God has clearly revealed Himself to the world in ways no one could miss. The million dollar question is how we will respond to this information. We can choose to honor Him and thank Him, or not. From Paul’s perspective, it’s that simple.

Knowing He Was God: What would be the expected response to this kind of knowledge? The choice has dire consequences. If people had chosen to honor God and thank Him in response to His revelation, the power of God for salvation would have been available to them. In contrast, the choice not to honor Him as God or give Him thanks resulted in futile and foolish thinking, a darkening of their hearts.

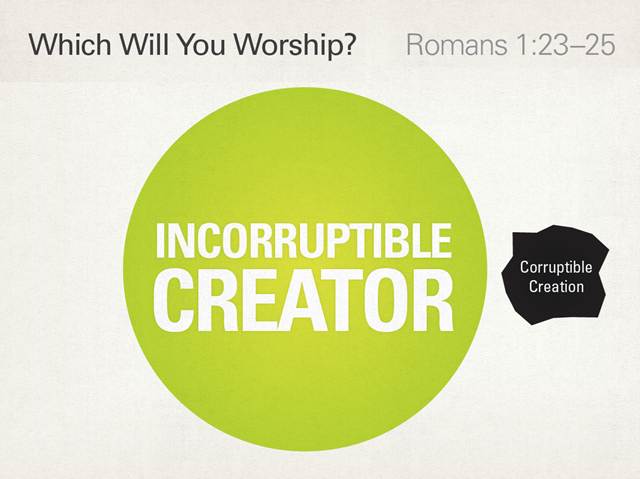

And what does this darkening and futility naturally lead to? Being wise in our own eyes (1:22). It also means that the “God-shaped vacuum” He created to draw us to Himself remains empty. Those who have rejected God find other things to worship in His place (1:23). After all, the existential questions about where we came from and the meaning of life don’t go away even if we reject the correct answer to them. So how do we make something that isn’t God seem godlike? We assign godlike qualities and characteristics to it. If someone tries to persuade you to worship something, chances are they are not going to call it a dumb idol or a false god. They are going to use every means possible to make it sound attractive. Think of a used car salesman trying to get you to drive one of his cars off the lot.

Paul uses the same kind of marketing strategy to build a case against exchanging the worship of God for something else. He contrasts the inherent unworthiness of these things with God’s worthiness to be worshiped, and he uses terminology that intentionally casts a negative light on the peoples’ decision to reject God. Instead of describing their behavior as a change—from worshiping God to worshiping animals and such—Paul casts the exchange as abandoning worship of the Immortal for images of things that are mortal. He draws a stark contrast between how God intended things to be and how things actually are. His contrasting terminology makes clear the lunacy of the exchange. He seeks to talk us out of going down this path by making it sound like a really bad idea—which it is.

Which Will You Worship? Like a good salesman, Paul makes his pitch by casting the choice between worshiping God vs. worshiping something else as a “no brainer” decision. He does this by reframing the choices and adding thematically loaded modifiers to create sharply contrasting antonyms. No matter how appealing that other thing might sound, it is still a horrible exchange.

Verses 24–25 outline the natural consequences of rejecting God as the object of worship. Their rejection of God as God led Him to give them over to their own lusts. Verse 25 reiterates the exchange described in 1:23, but now in starker terms. Instead of contrasting the mortal with the immortal, Paul now expresses the exchange in terms of origins. He contrasts worship of a created thing with worshiping the Creator. There is also a contrast between the glory of God and the image of the created things.

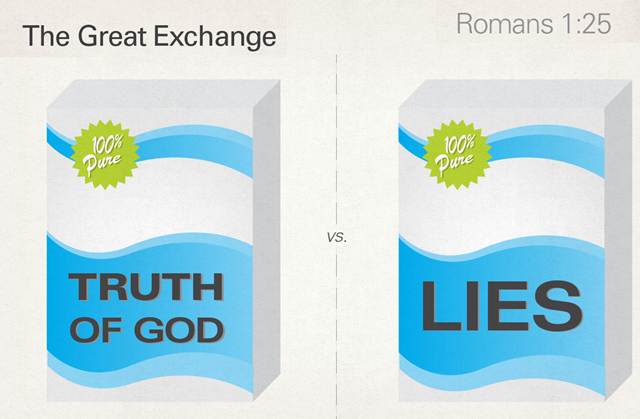

In 1:25 Paul characterizes the rejection of God in terms of truth and lies, and again he paints rejection in a bad light to make the desired outcome look even more favorable.

The Great Exchange: Paul “markets” his ideas to make the desired option sound much better than “the leading brand” of idolatry. He changes the contrast from the creator/creation to truth of God/lies. This is not an objective comparison, but “spin” designed to cast the act of forsaking God in as negative a light as possible.

The choice not to worship God as God does more than just focus our attention in the wrong direction. Recall Paul’s assertion in 1:21 that it leads to darkened hearts and futile thinking. This mental and spiritual posture manifests itself outwardly in our behavior. Paul provides specific examples and portrays them as “exchanges,” contrasting the order God had originally ordained with the unrighteous behavior that results from the rejection of His order. The people’s rejection is what provoked God to reveal His wrath (1:18).

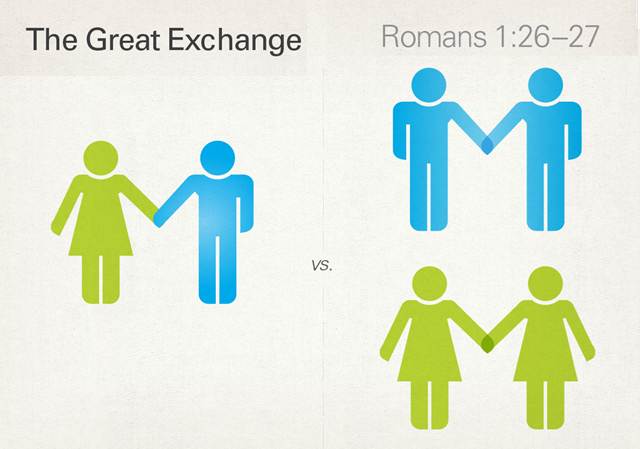

In verse 26, Paul’s metaphor contrasts people’s desire for each other and highlights another consequence of God handing us over to our own desires. The same Greek word for “desire” used in 1:24 is used again in 1:26, but with a different connecting word. Verse 24 introduces a conclusion summarizing the consequences resulting from 1:20, but 1:26 shifts from consequences to a cause/effect perspective. It focuses on their passions instead of the darkening of their hearts. The two are related; however, describing it in terms of passions sets the stage for a look at sexuality. The same Greek root translated “exchanged” in 1:23 and 25 is used again in 1:26 to describe the exchange of natural relations between men and women for unnatural ones. The repetition of these words cohesively connects these different images to one another.

The Great Exchange: The same root term found in 1:23 and 25 is used in 1:26 to describe the exchange of natural sexual relations for unnatural ones. This exchange of relations is portrayed as a natural consequence of people rejecting God as the object of their worship.

There is an important point to be drawn from how Paul frames this issue in Romans 1 and how it contrasts with how many present the issue today. The pendulum of public opinion has swung toward accepting same-sex relationships, a shift unlikely to change. This exchange of sexual identities falls under the general discussion of things against which God has revealed his wrath. The terms Paul uses in 1:18 are generally translated as “unrighteousness” and “ungodliness,” casting the problem in moral terms. However, it is interesting that this righteous/godly metaphor is not the one Paul uses to frame this exchange of God’s intended order. Rather than describing the behavior as immoral or ungodly, he describes it in terms of God’s natural order. It is unnatural—yet another rejection of the way God intended things to be. He also uses shame/honor language, describing the issue in terms of dishonoring passions (1:26) and shameless acts (1:27).

So why would Paul take this approach to what clearly seems to be a moral issue? If we claim to value attention to the details of the text, then we had better slow down and consider the implications of Paul’s wording. Some have claimed that what Paul has in mind here is not same-sex activity in general, but a specific kind. However, Paul’s language and the point that he draws from this argue against such a view. He includes men and women, rather than a subset of either. More important, the element of the behavior Paul focuses on is an exchange of natural relations for what is unnatural (1:27). Exclusion of certain kinds of same-sex behavior seems unlikely. But why would Paul make a shift from moral/immoral language to shame/honor language? The answer may well lie in how Paul chose to frame a potentially divisive issue.

Homosexuality would likely have been about as prevalent and accepted in Paul’s context as it is for us today, but not in the form of marriage or open relationships. Certain kinds of activity were regarded as more acceptable than others. This is not to say that the issue is less amoral than another kind of sin; it is not. After all, of all the potential sins Paul could have chosen to illustrate exchanging God’s way for some alternative, he chose this one. This is why we should pay close attention to how Paul chooses to frame the issue here. He does not describe it in terms of right and wrong behavior. Instead he uses shame and honor language to frame it as rejecting God’s natural order in favor of what is unnatural. Paul’s approach is less of a moral judgment and more of an observation regarding natural consequences of human decisions.

Despite the rising acceptance of “alternative lifestyles” and the clamor by today’s activists for our culture to celebrate diversity, Paul’s strategy here has a persisting relevance. There is still shame associated with alternative lifestyles, still a struggle with the reproductive disconnect it represents. Paul’s approach presents a more compelling appeal in our present context than the name-calling and placard-waving slogans we see in the media.

Sin is sin, despite the modern church’s adoption of an informal acceptability scale. Spiritual revival is characterized as a rejection of any sin, exchanging incremental repentance for total. The claims of hypocrisy by those outside the church can be traced at least in part to our inconsistent stance on sin in practice, despite what we might say in theory.

Stay tuned: Paul rejects the differentiation of sins in Romans 2:1 by showing how those who condemn others are guilty of the same thing. He shifts focus from behavior that immediately evokes moral indignation—for Jews regarding pagan, idolatrous Gentiles—to things that morally upstanding folks—like us—might do. In other words, he homes in on people who tend to think and act as if they have the Christian life pretty well figured out.

Paul is a master of framing issues and arguments to bring about a desired outcome. Throughout the book of Romans, he frames his argument based on whatever approach will best accomplish his purposes. We might benefit by taking a page from Paul’s playbook and rethinking how the church frames the issue of sexual sin (and sin more generally). It is no more sinful than lust, greed, hatred, or envy, just much less socially acceptable within the church. How we present an issue greatly affects how others receive it.

The final part of this chapter summarizes the consequences for those who reject God’s created order. The section begins in 1:27 where Paul introduces another “giving over” using the same Greek term from 1:24 and 26. Paul now looks at giving over to a darkened or debased mind rather than to degrading passions. This section provides something of a summary of the impact of rejecting God’s order to do “what ought not be done.” Nonetheless, Paul moves on to a list in 1:29–31.

The Great Exchange: In the final verses of the chapter, Paul reframes the issue in terms of throwing out God’s Word versus allowing it to renew our minds (12:3). Disregarding Scripture results in a debased mind rather than a renewed one, leading us to do what ought not be done.

Paul catalogs some horrible behavior in these verses. Envy, deceit, slander, insolence, prideful boasting—all can make life downright miserable as we suffer the consequences of other people’s decisions. Paul summarizes this section in 1:32 by boiling down the fundamental issue of sin. God’s revelation of Himself is sufficient for us to recognize our unrighteousness. But instead of agreeing and repenting, our sinful inclination leads us to deny or cover our sin. How? By getting others to join in so that our behavior doesn’t stand out as much. The height of sinful hubris is not simply sinning and knowing that the penalty for such things is death; no, it is encouraging and approving of others who do the very same things.

Let’s review how Paul develops his argument in Romans 1: He likely has a number of reasons for writing, but he chooses to unpack them in a certain way. Following his greeting, Paul states his intention to come visit the church in Rome in order to be mutually encouraged. He goes on to describe his shameless confidence in the gospel because God’s power and righteousness is revealed in it. Why is he so passionate about people hearing the gospel? Well, in addition to the revelation of God’s righteousness, there is the revelation of His wrath. The wrath is a consequence for those who reject God as God. People’s choice to exchange worship of the one true God for non-gods leads naturally to several other “exchanges.” In Paul’s view, the rejection of God’s created order leads to everything that is wrong in our world—and this rejection stems from the ongoing effects of sin. Therefore, God reveals His wrath against all the ungodliness and unrighteousness outlined following 1:18.

One of the effects of sin is that we often think more highly of ourselves than we should. Reading through the list of sins in 1:29–31—and the judgment that goes with them—it’s easy to see it as a “them” issue rather than an “us” or “me” issue. I can readily agree that “those kinds of people” deserve God’s wrath, not unlike the disciples asking Jesus if they should call down fire from heaven (Luke 9:54). It is much easier (and more common) to point the finger of blame at others instead of being convicted ourselves. Paul builds his argument so as to turn the tables in Romans 2:1. God pours out His judgment and wrath not only on the ungodly behavior of heathens, but even (perhaps especially) on that of people who confidently believe they have measured up to His righteous standard.

Sin and its consequences are universal problems, as Paul points out in the first section of the letter. In chapters 2 and 3, he will drive home the point that no one is exempt, but his main message here is that God will reveal His wrath against our rejection of His plan. We must understand this problem of sin before we can understand our need for the gospel and its power to bring about a restoration of God’s original plan. Remember that to Paul, the gospel offers much more than a means of forgiveness; it is the key to reestablishing the God-intended order and function of creation. The first step in grasping this bigger picture is to accept that we are all under God’s wrath. And for those who think they are somehow exempt, on to chapter 2!