Steven E. Runge, High Definition Commentary: Romans (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2014), 17–18.

Romans 1:8–17

As stated earlier, Paul’s fundamental intention in writing seems to be the exposition of the gospel rather than the announcement of his plan to visit Rome. Several times in the letter Paul begins a sentence with “first,” creating the impression he will add a number of related points—only there aren’t any others. Verse 8 is the first of these “firsts” in Romans, and it presents two possibilities: Paul intends to move on to other items in the list but gets distracted, or the “first” is rhetorically motivated to make it look like he is going to continue. In my view, the second option best explains what we see in the letter. It allows Paul to fake going one way so that he can go a different way, just like dodging the opposition in a ball game. Here’s what I mean:

We can see this in verse 8, where Paul presents what seems to be the first of several things for which he is thankful. But Paul gives thanks, but Paul mentions only one thing. This is not to say that Paul isn’t thankful for many things; it means he quickly moves on to the real purpose for writing by offering the reason he gives thanks (1:11–12).

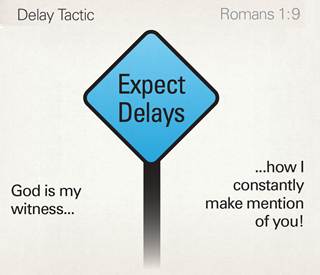

We find a different rhetorical device in 1:9: extra thematic information. This device separates Paul’s declaration that God is his witness from what it is that God witnesses. Since we already know which “God” he is referring to, the extra information shapes how we think about Him (and Paul). This delay draws extra attention to the final part of the sentence: Paul constantly making mention of the Romans in his prayers.

Delay Tactic: Paul begins a statement about God being his witness, but then interrupts this idea with a description of the God whom he serves. This extra descriptive information delays revealing what God is a witness of, drawing extra attention to it based on this delay.

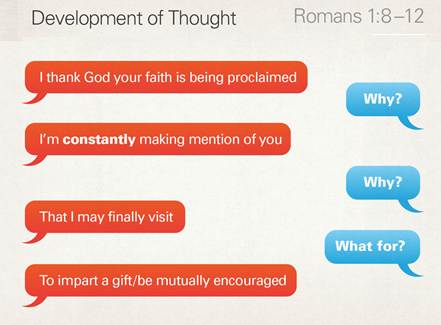

We find digressions into supporting material in verses 9, 10b, and 11. These “for” digressions serve the same kind of purpose as a rhetorical question, but without the need for interrupting the flow. Each statement strengthens the one immediately preceding. These statements not only offer support, they also sidestep off the main line of argument onto what can become an embedded theme line. This is just like when we go off on a tangent in the middle of a story, filling in important information before coming back to the main storyline. However, in the case of Romans, 1:17–18 begin an extended digression that continues all the way through the end of chapter 4. Then 5:1 resumes the argument suspended in 1:16–17.

By beginning the thanksgiving statement in 1:8 with “first,” Paul creates the idea that he’s going to provide another thing related to the list, but his digressions remove him ever further from the list. He never returns to his list of things for which he is thankful. Paul’s feint here is rhetorically motivated, based on his larger purpose of announcing his visit and providing an exposition of the gospel. Paul’s desire to visit becomes the big idea for the balance of this section, and all the rest simply serves to strengthen this assertion.

Development of Thought: Paul introduces a series of sentences using “for,” with each one providing support for the preceding sentence. Each of these statements digresses off the main argument line. The longer the series, the bigger the digression. These “for” statements create a specific development of thought (just as using rhetorical questions would), by providing a rationale or motivation for what precedes.

In 1:11 Paul seems to misstate his motivation for wanting to visit Rome before he corrects it in 1:12. This kind of mistake is quite common when speaking, since there is so little time between planning what to say and actually saying it. But when we write, things are different. We devote time to “chewing on the pencil” while we plan, and we make fewer misstatements than we do when speaking. Even back in Paul’s day, it was possible to erase and make corrections. This means we might better understand 1:11 as an intentional statement rather than a misstatement.

Remember from the introduction that Paul’s lack of a relationship with the Romans likely leads him to use a less-direct approach than we find in his other letters. One way to communicate his humble stance to the Romans is to intentionally overstate something and then correct it. Lawyers do the same kind of thing in court, asking questions they know are not allowed and then retracting them. These are not mistakes, but calculated decisions to achieve certain effects. After all, the jury still hears the question! We have good reason to believe this is Paul’s intention, since he uses rhetorical devices elsewhere to mitigate his directness. The shift from 1:11 to 1:12 shows how Paul transitions his role from someone who exercises authority over the Romans to someone who functions more as a peer seeking mutual encouragement. Paul reinforces this sense of commonality at the end of the verse by adding “both yours and mine.” Even so, the Romans would have had little doubt about whose faith he had in mind.

Paul begins a new point in 1:13, addressing why he hasn’t yet visited the church in Rome. He uses an attention-getting metacomment—“I don’t want you to be unaware”—which draws attention to what he is about to say. He could have skipped the metacomment, saying only that he had often intended to visit, but that statement would have lacked the same rhetorical punch.

Remember that all facets of this discussion—Paul’s being prevented from coming and his intentions in seeing the Romans—support his big idea of wanting to visit. In other words, it is all a digression rather than an advancement of the main argument. The first word in 1:15 signals Paul’s return to the main idea of this section, just like someone saying, “So anyhow” or “as I was saying,” to resume where they left off.