Steven E. Runge, High

Definition Commentary: Romans

(Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2014), 35–46.

Romans 2

Romans 2:1–16

Chapter divisions in the Bible are useful for navigation, but they can be troublesome when it comes to tracking the flow of an argument. Paul does begin a new section in Romans 2—but one that builds directly on the latter half of chapter 1. He begins with a “What were you thinking?!” kind of statement that assumes we know Paul is talking to the Romans. Paul fills in the “who” by using a series of support clauses that digress from the original question of “Who are you?”

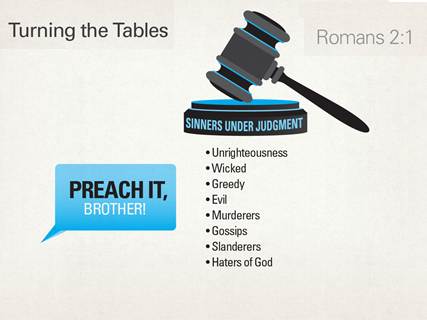

Even though in most English Bibles, 1:18–32 is labeled with a heading like “the guilt of humankind,” not everyone who reads this passage would believe it applies to them. Paul lists some pretty egregious sins, and our tendency to think more highly of ourselves than we should often leads us to deflect things we should take to heart. After all, who hasn’t envied or expressed hatred? But in the broader context, it’s easy to see how people who had not committed the big sins could exempt themselves entirely. They think, “Boy, I’m sure glad I don’t do horrible things like that!” Paul seems to have anticipated that some Jewish readers would exempt themselves from his indictment of seemingly pagan Gentile behavior. But excluding themselves from the condemnations of chapter 1 sets them up to get zinged in 2:1. Paul lists things everyone can agree are wrong—only to turn the tables on the people who exempted themselves.

Turning the Tables: We have a tendency to think more highly of ourselves than we should; we think we are generally good people. When Paul presents a list like this, our first inclination is to think of other people who fit the descriptions. But rarely do we place ourselves at the top of the list. There is always someone more evil, more vile, right? Paul uses the list of sins in Romans 1:29–31 to set the stage for a reversal in 2:1.

Remember, sin is a universal problem; it does not discriminate, no matter what kind of wishful thinking might lead us to believe otherwise. Rather than directly addressing the “holier than thou” crowd and trying to win a conviction, Paul uses a backdoor approach. How? He gets them to heartily affirm that a whole host of things are deplorable and then shows them that they do the very same kinds of things. Conclusion? They (and we) are just as much under the impending wrath as the heathen Gentiles who likely came to their minds.

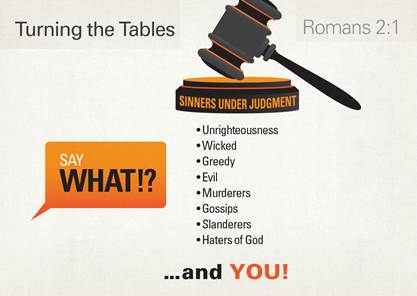

Turning the Tables: Paul’s condemnation of clearly sinful behavior in 1:29–31 would not draw opposition, but agreement, especially from those who were confident in their righteous standing before God. He turns the tables in 2:1–3 by declaring that “you” are under judgment, identifying “you” as those who pass judgment on others and do the same things.

Paul finally identifies “you,” three times in quick succession (2:1, 2, and 3). “You” here refers to people who judge others for doing something they do themselves. He exploits the human tendency toward pride to emphasize that we all face the same impending judgment, thus we all have the same need for reconciliation with God. We may not have committed the heinous sins listed at the end of Romans 1, but no one is sinless. We display the height of hypocrisy when we judge others for what we do ourselves.

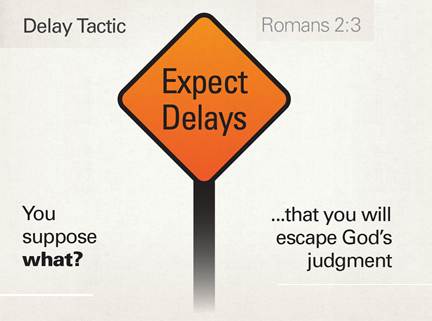

Paul uses the third repetition of “you who pass judgment” as a means of delaying the key part of a question in 2:3. It separates the “do you suppose” from what is supposed. Since Paul has already identified his intended audience twice, the third repetition serves as a rhetorical delay tactic, drawing extra attention to the important idea of supposing to escape God’s judgment. It also reinforces his characterization of his audience as hypocrites who condemn others for doing what they themselves do.

Delay Tactic: Paul begins this section with a series of statements addressed to “you” without clearly identifying the people to whom he refers. He identifies them as “you who pass judgment on others and do the same thing,” then repeats this same information twice more. The final time this information functions as a detour of sorts, separating the question of what is supposed from what is supposed. Since Paul has already identified his intended audience in 2:1 and 2, the repetition in 2:3 serves the rhetorical function of causing a delay to draw attention to the what: “escaping judgment.”

Paul’s success in arguing for the gospel’s surpassing importance through the rest of the book is contingent on the recognition that everyone shares the same need. No one is exempt, no matter what. Paul devotes the rest of this chapter to fleshing out the “no matter what.” Even though Paul addresses all people, it is fair to assume that good Jews (or modern Christians) would exclude themselves from those facing impending judgment. Why? Because no self-respecting Jew would participate in sexual immorality, murder, or most of the other things Paul lists. And if they had any doubt about their behavior, they could appeal to their special covenant relationship with God. This is precisely why Paul transitions here to dispelling the notion that Jews and Gentiles are somehow held to different standards. To really understand the gospel, we need to understand that everyone is in the same predicament.

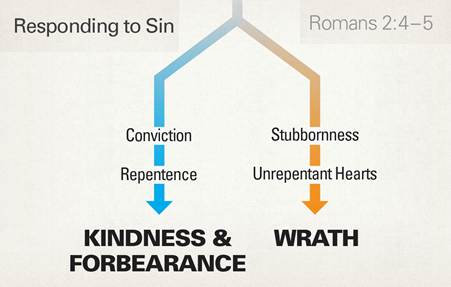

While Paul uses verses 1–3 to highlight the folly of thinking we can somehow escape God’s judgment, in 2:4 he turns to the implications of passing judgment on others for the things we do ourselves. The hypocrite in question wants to condemn sinners rather than pardon them or extend grace. After all, doesn’t their sin deserve to be judged? Yes, but the hypocrite is only looking at one side of the proposition. They ignore the fact that they are behaving in the same way. Paul claims that God’s kindness, forbearance, and patience are intended to bring about repentance. The hypocrite lacks these qualities, and Paul characterizes the hypocrite’s decision to condemn as despising God’s kindness and patience. This comes as a slap in the face to those who expect God to respond to sin with the same righteous indignation they do.

We often try to put God in a box, to think of Him and His intentions monolithically. However, doing so can be problematic. Thinking of Him only in terms of His love and acceptance diminishes our sensitivity to sin and its consequences to our relationship with Him. Conversely, viewing Him as focused solely on judging sinners ignores His desire to see us repent. It all boils down to how we respond to our sin.

Responding to Sin: There is a tendency to think of God monolithically, as either kind and loving or as harsh and judgmental. In reality, both views are true. One of the keys to determining which aspect of God we experience is our response to the recognition that we have sinned and therefore face God’s wrath. Paul outlines two paths. Those who acknowledge their sin and repent experience God’s kindness, forbearance, and patience as they walk by faith. Those who reject the conviction of sin and refuse to repent face the very wrath described in Romans 1. Our perspective on God’s character relates directly to our response to sin.

Hypocrites are deceived in several ways. First, they are wrong in thinking they can somehow escape God’s wrath; they are sinners just as much as those whom they condemn. Verse 5 makes clear they are not escaping wrath, but storing it up instead. Second, God doesn’t write people off just because they have sinned. In fact, in God’s economy, His kindness, forbearance, and patience are intended to bring about a change of heart in the sinner. He is not letting them off the hook, but merely giving them an opportunity to change.

In verses 6–12, Paul makes a complex series of statements examining different sides of the same issue. In Greek, this section is one big relative clause describing God. It is not meant to narrow down which God Paul has in mind; instead it shapes how we should think about God in this context. Why? To draw a clear contrast between those pursuing a self-centered life and those who devote themselves to serving the Lord. Paul develops this contrast by characterizing God as the one who will respond appropriately to each group.

We can take one of two paths, each with a different outcome. Paul is concerned here not with divine sovereignty versus free will (see 9:19), but with the two potential outcomes. No matter which path we take, we will be judged by God; there is no way around it. Paul makes clear that a person’s lineage as a Jew or Gentile will not affect the outcome, since God uses the same standard to judge everyone. It is not a matter of merely possessing the law, but of obediently living it out.

This raises an important question in the mind of those who pride themselves on their law-keeping. The law was given to the Jews, not to the Gentiles. Remember the list of sinful behavior from Romans 1:24–32? These are the kinds of behaviors that were expected of heathen Gentiles, not Jews. So how is it that a Gentile could somehow be accepted by God? We see Paul begin moving in that direction in 2:14. But first he needs to make clear that our response to the conviction of sin is what determines our future with God.

Remember that the problem of sin is described at the end of Romans 1 as a rejection of God’s created order. If we continue to reject His order, we will eventually become stubborn and unrepentant, the darkening of the heart Paul describes in 1:21–23. But instead of responding with immediate judgment, God responds with forbearance and patience. Why? Because He wants us to turn back to Him instead of continuing in our stubborn rebellion. Remember, He created us for a purpose, and that purpose has been derailed by sin. God’s desire is that we would return to Him instead of pressing ahead down the wrong path. We need a complete change of direction—repentance. If we do not repent, judgment and wrath await us. But if we are willing to humble ourselves and repent, to respond favorably to God’s kindness, forbearance, and patience toward us, we can expect a completely different outcome.

We need to take God out of the little boxes we have constructed for Him and allow Him to be who He is. Yes, He is holy and pure, and thus our sin separates us from Him. But this is not the whole picture. He extends His kindness and patience toward us to lead us to repentance. Why? Because He created us and everything else for His purpose (see 9:19). Just because sin entered the world doesn’t mean that God’s plans have changed. It simply means we have mucked things up, and He intends to return everything to what He originally intended. Even so, we determine what our future has in store by how we respond to His overtures. His holiness cannot ignore sin, but His compassion and patience prevent Him from abandoning His original plan altogether. There is a window within which things can change, but it will not always be open (see Heb 4:6–7).

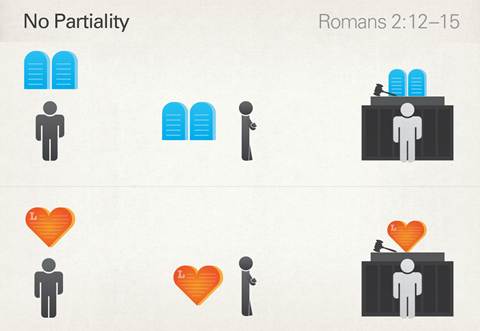

In Romans 2:11 Paul raises the issue of partiality, rejecting any notion that God plays favorites. In the verses that follow, Paul offers support for his claim that God is impartial, thus opening an unsettling discussion about the relationship between the law and righteous behavior. Paul introduces two categories of people in 2:12: those with the law and those without the law. Both groups commit sin; the key distinction is whether they do it while being under the law or not. Conventional wisdom suggests that having God’s law might create some special status for those who possess it. However, the opposite seems to be the case.

When reading 2:12, we may think it sounds as if those who are not under the law are not held accountable to it. The corollary seemingly holds as well: Those who are under the law will be judged by it. In this sense, it may appear that people without the law stand a better chance than those who have it. We all know the saying that “possession is nine-tenths of the law,” but God’s economy doesn’t work that way. As Paul explains in 2:13, it’s not possessing the law but keeping it that determines our righteousness. For the Jew who believes possession conveys some special status within the covenant community, this idea would be shocking. Jew and Gentile alike must follow the law to be declared righteous by it. Both face the same dilemma: Sin creates a barrier to having a righteous standing before God (2:16).

But this presents a different problem. If you cannot follow a code or law because you don’t have access to it, wouldn’t you—in this case, the Gentiles—be considered unrighteous in God’s sight? Paul drops his next bombshell on Jewish believers with his words in 2:14 by introducing a state of affairs regarding the Gentiles. Although he has already established the identity of the Gentiles, he adds extra thematic information here to re-characterize them as “the ones not having the law.” He even changes the word order in Greek to emphasize their “lawlessness.” It turns out that things might not be as simple as they first appear to be.

What if the Gentiles, who do not have the law, are somehow able by nature to keep it? Such a scenario sounds impossible, but Paul nevertheless asks the question. If keeping the law is more important than having the law, then maybe the Gentiles are not in such a bad place after all. Paul says that those who keep the law—even though they don’t have it—are a law unto themselves. Paul is not claiming some new path to justification; he’s making an important point about the limitations of only possessing the law.

In 2:15, Paul elaborates on these law-keeping folks without the law. How could they possibly keep a law they do not have? From God’s perspective, the law that was given to Moses is not the only code that can convict a person of sin. Rather, there is a law that is written on people’s hearts. This law correlates to their consciences, the thoughts of which accuse and even defend them (see 1:19–20). But Paul goes further, claiming that God will prove this on the day when He judges people according to the gospel message. In this way, the law to which people have access determines the basis on which they will be judged.

No Partiality: In God’s judgment, possession is not “nine-tenths of the law.” We will be judged by our obedience to the law, whether that be God’s law revealed to Israel, or whether it is law written upon the heart. Thus there is no distinction between Jew and Gentile on the basis of possessing the law of Moses.

So what is the point of this discussion about an alternative kind of law? First, it is the keeping of God’s law, not the possession of it, that determines one’s righteousness on the day of judgment. And Paul is not referring only to the Mosaic law, but to the law that is written upon people’s hearts. Now before you call out heresy, let’s understand what is happening here. Paul’s discussion says nothing about whether people are actually able to obtain a righteous standing on their own on that final day. His goal here is simply to posit two different tracks for judgment. Both—not just the one based on possession of Mosaic law—lead to the same place.

Both Jews who have received God’s revealed law and Gentiles who live according to what is written on their hearts will be judged on the basis of their obedience to that law or code in the day of judgment. In these verses, Paul establishes that everyone, regardless of whether they have a revealed law, is in the same predicament regarding final judgment. Particularly in verse 17 and following, Paul reiterates the need for keeping the law in order to be declared righteous by it. But his modest goal here is to demonstrate that Jew and Gentile alike have something to which they are held accountable, and no one has an excuse (1:20).

In this passage, Paul demonstrates that people have exchanged God’s created order in favor of their own paths. Jews who reject God are not exempt from this condemnation; having the law does not give them a special status. Even the Gentiles have a law written on their hearts and will be held accountable to it. Keeping the law is what matters, regardless of whether it was revealed from Sinai or given as a type of moral compass. Both groups have an equal opportunity to respond, and that response is the basis for God’s judgment.

So far, Paul has overturned a few notions cherished by some in his Jewish audience. For the rest of this chapter, Paul tackles remaining counterarguments regarding special status being reserved for Jews who possess the law. He holds Gentiles up as a foil against which to contrast Jews who gives lip-service to law-keeping, but fail to obey. Again, Paul’s point is not to answer whether anyone can perfectly keep the law. He already made clear that the consequences of sin will come in the day of judgment, and he will address the issue more fully in chapter 3. Paul’s key point here—as shocking as it seemed to his audience—is the critical role law-keeping plays for both Jews and Gentiles.