Steven E. Runge, High Definition Commentary: Romans

(Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2014), 55-60

Romans 3:1–8

In Romans 2, Paul makes several significant claims that undermine the notion that God favors Jews more than Gentiles. Following his claim in Romans 2:11 regarding God’s impartiality, Paul asserts that the Gentiles have the same opportunity as the Jews to be declared righteous, based on their following of the law that God has written on their hearts. Conventional wisdom said that the Jews held an advantage since they were entrusted with the law God revealed to Moses. Unless Gentiles converted to Judaism, they were not considered part of the covenant community. Again in 2:25–29, Paul repeats that God places equal or higher value on obedient Gentiles than the supposedly advantaged Jews. Paul claims it is the circumcision of the heart that matters—what is done by the Spirit rather than by human hand. The Jewish community would have been completely unsettled by this idea.

Contrary to what some might think, Paul is not seeking to throw Judaism under the bus, but rather to level the playing field for his argument about the gospel. Paul will highlight Israel’s special place in God’s plan later (see 9:1–5; 11:17–21), but not quite yet. For now his audience needs to understand that all are under impending judgment for sin and share the same need for reconciliation with God. But to gain a wider hearing, Paul deconstructs the supposed advantages of being a Jew. He even uses the (non)listing of advantages to do this. Here’s what I mean:

Throughout Paul’s letter to the Romans, he uses rhetorical questions—questions he answers himself—to introduce his next big idea. Nevertheless, rhetorical questions still provoke us to think about potential answers, even if we never state them out loud.

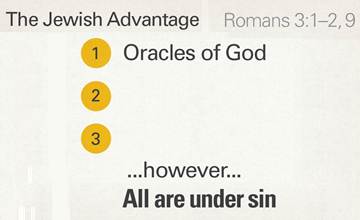

Paul rhetorically asks what the advantage is for Jews or the use of circumcision in light of this notion that Gentiles can ostensibly achieve the same kind of favor before God without these things. His answer is the Greek equivalent of Americans saying, “Oh, there’s tons of reasons!” “Much in every way” creates the expectation that a substantial list of reasons will follow. He confirms this by beginning with “first” and using a Greek particle whose sole purpose is to make readers expect at least one other related element. We find a similar clustering of these forward-pointing markers at the beginning of the list in 1 Cor 12:28. Why state “first” unless you intend to have a second and so on?

Alternatively, some have claimed that Paul meant to go on with a list, but that he got sidetracked or forgot what he was planning to say. While either is possible, it seems unlikely based on the kind of rhetorical strategy Paul uses. Remember what he’s doing here: reminding Jews that they are in exactly the same boat, spiritually speaking, as Gentiles. Although their covenant status with God is significant (as Paul drives home in Romans 9 and 11), it can’t bridge the gulf sin creates.

In light of Paul’s rhetorical strategy in Romans 2, we have good reason to understand this one-item list as part of his larger purposes. Think about it: He creates the expectation that a whole list will follow, but if he had listed that many advantages, it would have undermined his task at hand.Null and Void? Paul introduces his next big idea using a rhetorical question. Have the promises that have been trusted for so long been nullified? Is there some kind of fine print that would allow God to renege on His promises because of Israel’s disobedience? No way.

Paul has significantly undermined concepts that have traditionally been understood to set the Jews apart from, and perhaps even above, the Gentiles. He argues that Gentiles could achieve the same kind of relationship with God by responding obediently to the law written on their hearts. He also makes clear that God’s wrath has been revealed against all unrighteousness, not just that of the Gentiles.

Paul now (temporarily) restores his Jewish audience’s confidence regarding their unique role as God’s covenant people. In Romans 11, Paul develops the concept that only a remnant of Israelite believers—not all of the Israelite nation—is part of the covenant community and will be saved (11:5, 25–26). This claim is grounded in his threefold assertion that not all of physical Israel is actually Israel (9:6–8). But the complexities regarding national hardening, sovereign choice, and being descendants of faith come later. For now, Paul simply affirms the truth of God’s faithfulness in principle and moves on. There is more groundwork to be laid regarding the relationship between faith and justification before God.

Paul first discusses the relationship of faith and belief to God’s response. Notice how he frames verse 3. He does not ask whether some have not believed, but rather what will happen to those who don’t believe. He presupposes that disbelief exists and that it might affect the community’s covenant relationship with God. Paul’s response includes a quote from Psalm 51:4 that affirms God’s justification for judging sin rather than the security of the sinner when he is judged. So instead of affirming that the nation will be saved on the basis of the covenant alone—without belief—Paul argues to the contrary. Salvation involves more than simply law-keeping membership in the covenant community. God always intended that final judgment would be based on faith in His provision.

In verses 5–8 Paul outlines his complex logical argument exploring some of the implications of unrighteousness. Paul does not advocate unrighteousness here; he derails the notion that our unrighteousness makes God’s righteousness stand out all the more.

This question stems from the notion that people exist to bring glory to God. If this concept is true, then perhaps sinning more might be a good way to put God in a better light. Paul answers in 3:6 with the same “No way!” line he uses throughout the book. He also makes clear at the end of 3:5 that this is purely a hypothetical notion that seems logical from a human perspective.

However, there are problems with this proposed strategy. The first concerns why God created us in the first place—to be in fellowship with Him. The choice to sin made that impossible. In Romans, Paul details God’s plan to redeem the relationship (and the world) from the destructive consequences of sin and bring everything back to its original order. A big part of that restoration involves judging sin and removing it from His creation.

Since judgment involves punishment for sin, Paul rhetorically asks why the sinner is condemned if the sin makes God’s glory abound. He rephrases this concept in 3:8 in the form an exhortation to do evil so that good may come about. Of course, Paul is not advocating this course of action, but by proposing the opposite behavioral extreme, he lays the groundwork for valuable lessons: There are no benefits to sin and evil, whether white lies or wanton debauchery. Sin accomplishes nothing but storing up more wrath for the day of judgment.

Paul’s hypothetical notion here may sound outrageous, but not so much as you might think. Attitudes toward sin change over time. As a young college student seeking God, I felt oppressed by my sin and the baggage that came with it. When I prayed to receive Christ, my greatest motivation was to obtain forgiveness and freedom from the guilt. But things can change. Not every sin is so overtly oppressive that we long to escape it. We can even come to regard sin as a part of who we are—a personal quirk that others just need to accept, and something we do not want to give up. Under those circumstances, we may start looking for reasons to justify our sin. The disobedience Paul describes in Romans is likely not self-indulgent sin; all sin breaks our fellowship with God. No matter our motivations or justifications, we provoke the same consequence if we continue in sin.

The Jewish Advantage: Are there advantages for the Jew? Paul’s answer in verse 2 makes it sound as if he is going to list off many, but his list includes only one item. It is not that there aren’t advantages (see Romans 9:4–5), but listing them here does not serve Paul’s purpose. He is using a rhetorical feint.

Paul does indeed provide a list of advantages for the Jews, but not until 9:4–5. Why there and not here? Because in chapter 9, Paul prepares to challenge the Gentiles not to think too highly of themselves. After all, if God removed branches to graft the Gentiles into His family, He can just as easily prune them back again (11:17–21). Eventually Paul takes the Gentiles down a notch or two, but here he focuses on the Jews.

Paul introduces the next point in his argument in 3:3, again using a rhetorical question. We may struggle to tell from most translations, but Paul uses an embedded argument in verses 3–8 to support his assertions in verses 1–2 that there are indeed advantages for the Jews. So why aren’t they experiencing God’s blessing? Could it be that some of them were unfaithful? That would have an impact on God’s response to them. The answer is the first of many “No way!” responses through the book. Paul intentionally asks flawed or incorrect questions so he can slap them down with a correct response. His questions are like asking if there is any fine print in God’s promises that would allow Him to back out and nullify His covenant.

Null and Void? Paul introduces his next big idea using a rhetorical question. Have the promises that have been trusted for so long been nullified? Is there some kind of fine print that would allow God to renege on His promises because of Israel’s disobedience? No way.

Paul has significantly undermined concepts that have traditionally been understood to set the Jews apart from, and perhaps even above, the Gentiles. He argues that Gentiles could achieve the same kind of relationship with God by responding obediently to the law written on their hearts. He also makes clear that God’s wrath has been revealed against all unrighteousness, not just that of the Gentiles.

Paul now (temporarily) restores his Jewish audience’s confidence regarding their unique role as God’s covenant people. In Romans 11, Paul develops the concept that only a remnant of Israelite believers—not all of the Israelite nation—is part of the covenant community and will be saved (11:5, 25–26). This claim is grounded in his threefold assertion that not all of physical Israel is actually Israel (9:6–8). But the complexities regarding national hardening, sovereign choice, and being descendants of faith come later. For now, Paul simply affirms the truth of God’s faithfulness in principle and moves on. There is more groundwork to be laid regarding the relationship between faith and justification before God.

Paul first discusses the relationship of faith and belief to God’s response. Notice how he frames verse 3. He does not ask whether some have not believed, but rather what will happen to those who don’t believe. He presupposes that disbelief exists and that it might affect the community’s covenant relationship with God. Paul’s response includes a quote from Psalm 51:4 that affirms God’s justification for judging sin rather than the security of the sinner when he is judged. So instead of affirming that the nation will be saved on the basis of the covenant alone—without belief—Paul argues to the contrary. Salvation involves more than simply law-keeping membership in the covenant community. God always intended that final judgment would be based on faith in His provision.

In verses 5–8 Paul outlines his complex logical argument exploring some of the implications of unrighteousness. Paul does not advocate unrighteousness here; he derails the notion that our unrighteousness makes God’s righteousness stand out all the more.

This question stems from the notion that people exist to bring glory to God. If this concept is true, then perhaps sinning more might be a good way to put God in a better light. Paul answers in 3:6 with the same “No way!” line he uses throughout the book. He also makes clear at the end of 3:5 that this is purely a hypothetical notion that seems logical from a human perspective.

However, there are problems with this proposed strategy. The first concerns why God created us in the first place—to be in fellowship with Him. The choice to sin made that impossible. In Romans, Paul details God’s plan to redeem the relationship (and the world) from the destructive consequences of sin and bring everything back to its original order. A big part of that restoration involves judging sin and removing it from His creation.

Since judgment involves punishment for sin, Paul rhetorically asks why the sinner is condemned if the sin makes God’s glory abound. He rephrases this concept in 3:8 in the form an exhortation to do evil so that good may come about. Of course, Paul is not advocating this course of action, but by proposing the opposite behavioral extreme, he lays the groundwork for valuable lessons: There are no benefits to sin and evil, whether white lies or wanton debauchery. Sin accomplishes nothing but storing up more wrath for the day of judgment.

Paul’s hypothetical notion here may sound outrageous, but not so much as you might think. Attitudes toward sin change over time. As a young college student seeking God, I felt oppressed by my sin and the baggage that came with it. When I prayed to receive Christ, my greatest motivation was to obtain forgiveness and freedom from the guilt. But things can change. Not every sin is so overtly oppressive that we long to escape it. We can even come to regard sin as a part of who we are—a personal quirk that others just need to accept, and something we do not want to give up. Under those circumstances, we may start looking for reasons to justify our sin. The disobedience Paul describes in Romans is likely not self-indulgent sin; all sin breaks our fellowship with God. No matter our motivations or justifications, we provoke the same consequence if we continue in sin.