Steven E. Runge, High

Definition Commentary: Romans

(Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2014), 65–70

Romans 3:21–26

There have been significant debates recently regarding what Paul means by “works of the law.” Does he intend to signify a works-based view of salvation, one that is earned rather than received by faith? Or does he refer to something else, to covenant fidelity within the Jewish community? Paul does not offer a clear definition; he assumes his audience knows the meaning of this phrase. It is clear that one simple meaning will not fit every context in Romans; the issue cannot be resolved, but I will comment on what is or is not possible in a given context. In my view, one of the more significant issues Paul addresses in Romans is what the Gentiles must do to respond to the gospel. Paul tackles this matter more for the sake of Jewish believers than for the Gentiles who had already responded in faith. In some contexts, in which the focus is clearly on final judgment for sin, keeping the law is seen as being related to the outcome of that judgment. But there are other contexts in which this is clearly not the case, where the focus is more on inclusion versus exclusion from the body of believers.

In 3:20–21 Paul brings these two notions together. In 3:20, he seems to very clearly connect works of the law to the need for being declared righteous, most likely at final judgment. However, in 3:21, he focuses on the revelation of a righteousness that is apart from the law, but about which both the law and prophets testify. Paul’s language in this verse seems clearly focused on inclusion versus exclusion. The revelation of this new righteousness is not just for those in the covenant community, who demonstrate their membership through their law-keeping. Thus, the righteousness is not just for the Jews or those willing to convert to Judaism. Even those outside the covenant community have access; covenant membership is not a prerequisite for responding in faith to the gospel. Why? There is no distinction, because everyone has sinned, and the gospel message is for all sinners without distinction. In 4:12–16, Paul appeals to Abraham as evidence that there never has been a distinction—God’s plan all along has been that this message would bless all nations through Israel’s proclamation of it. Law-keeping was not a prerequisite to faith, but rather an obedient response.

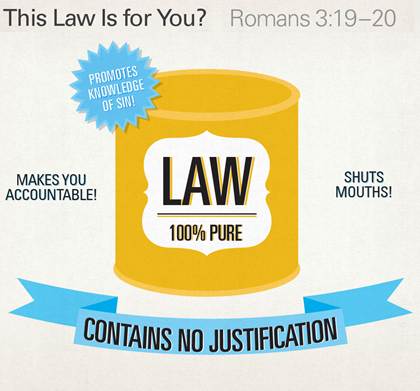

In 3:19–22 Paul juxtaposes the law with this new righteousness of faith God has revealed in Jesus Christ. He does not spell out two separate lists. Rather, he highlights key details about each form of righteousness. The extra thematic information characterizes each so as to maximize the differences between them. The description of the law focuses on its divine purpose and intentional limitations.

This Law Is for You? These are very familiar verses, but they contain a tremendous amount of important theological content. Paul adds detail to “brand” the law, shaping how we think about it.

God never intended for the law to provide a means for us to obtain a righteous standing before God, nor do we have any indication this is how Jews regarded the law in the Old Testament. The law revealed God’s holy character by promoting our knowledge of sin. Knowing we are sinful, we have no grounds for criticizing God when He holds us accountable.

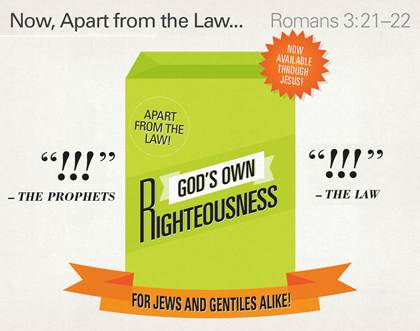

These are also very familiar verses for most of us, making it easy just to gloss over the important details being highlighted. If we think of all of this detail as if it were part of an ad campaign, Paul’s intention is to influence our buying decision: to buy into God’s righteousness rather than one obtained through the law. He marks the turning point in verse 21: “but now, apart from the law.…” The description of God’s righteousness revealed in Jesus sharply contrasts with Paul’s characterization of the law. This righteousness offers a solution to the problem of sin, not just knowledge of it.

Now, Apart from the Law: These familiar verses convey significant theological content. The details that Paul provides shape how we think about God’s righteousness, not unlike how advertisements highlight key selling points.

Paul explains that this righteousness is not some new thing, although it has been anticipated throughout the Old Testament. Instead of restricting this righteousness to a chosen group, God has made it freely available to all who believe in Jesus. Paul characterizes it in 3:21 as an “apart-from-the-law” righteousness, an idea that will be fleshed out in the following chapters. In 3:22, Paul restates the “righteousness of God” as if there is a need to add more detail about which righteousness he has in mind. He repeats this phrase to emphasize its importance and prompt his audience to read the verse as if it were a second pass at the same idea: God’s righteousness has not only been revealed and witnessed to, but it is a righteousness of God through faith rather than some other means, and it is available to all who believe, not just to the covenant community of Israel.

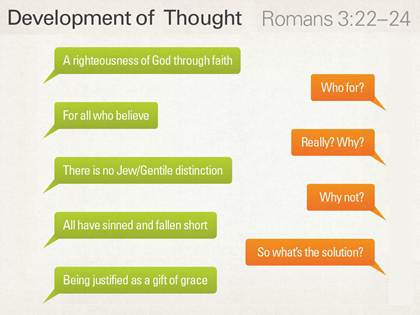

Paul supports the universal availability of this righteousness with the assertion in verse 22 that there is no distinction among people. How is it that no distinction can be made? He offers further support in 3:23, reiterating what has already been demonstrated. All have sinned and fallen short; therefore, all share the same need for righteousness from God. Thankfully, it is available to all who believe, without distinction being made between Jew and Gentile. Paul elaborates in verse 24 about how this righteousness actually comes about: The justification has been made available by a gift of God’s grace. This grace is manifested in the redemption available in Jesus Christ. In 3:24 Paul states what is essentially a corollary to the claim that all fall short of God’s glory, that this is not the end of the story.

Development of Thought: Each of the “for” statements Paul introduces adds information to support his preceding statement. In English we would more naturally use a series of rhetorical questions to achieve the same effect.

In Greek, the way Paul structures verses 22–24 compares to how a dialogue might unfold. Each support clause plays the rhetorical role of addressing a possible question and redirecting the flow of the argument. By reframing things in light of the question being addressed, Paul makes it easier to track the development of his argument.

In 3:25, Paul provides a thematically loaded description of Jesus, even though it is already clear about whom Paul is speaking. This characterization evokes a complementary picture of Him as God’s means of atonement for all those who believe. This atonement provided an important public demonstration of God’s righteousness. Why was it important?

If God had simply ignored the sin and swept it under the rug, He would have acted unjustly. His character demands payment for the sins committed; anything short of that would have impugned His character. Our lives are the obvious payment for sin (6:23). But God chose a different path, one in which he remained just and also justified us. This option was very costly, since it required the death of His Son as the atoning sacrifice.

Just and Justifier: What if God had simply swept our sin under the rug and ignored it? He would be unjust for leaving sin unjudged, for not addressing its penalty. But providing His own righteousness enables Him to be both just and the one who justifies us.

Even though sweeping our sin under the rug seems like a viable option from a human perspective, it is not from God’s. The sin we incur demands payment. Yet God exercises extreme forbearance and chooses to defer His wrath from the time of the fall until Jesus’ death and resurrection (and beyond) to provide an alternative to our death. In 3:25–26 Paul makes clear that God’s plan of sending Jesus to die on our behalf was not intended only to achieve our justification. It allowed God to satisfy the penalty of sin while remaining just regarding His righteous requirements.