Steven E. Runge, High Definition

Commentary: Romans

(Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2014), 73-79

Romans 4:1–8

Verse 31 functions as something of a hinge as Paul closes off one discussion and opens the next. He introduces this section with a connecting word that indicates he is about to offer a summary or thesis drawn from the preceding discussion. He frames this summary as a rhetorical question: Has the law somehow been nullified based on the exclusive role of faith in justification? Paul provides another resounding “No way!” in response, but then moves on to another question in 4:1. Because Paul is asking yet another question, it may seem that he is moving on to another topic. However, the Greek connecting word in 4:1 indicates that he is building on the preceding argument. The potential of Abraham’s boasting in 4:2 builds directly upon the rhetorical question of 3:27.

How does it build? Well, Paul is going to discuss the question about the nullification of the law, but instead of providing a logical argument, he uses Abraham as a case study to make his point. But more than just offering a case study, Paul uses this discussion to drive home the continuity of God’s plan for humanity from the beginning. The righteousness of God revealed in the gospel is not a new, last-ditch effort to redeem people. Rather, it has been attested by the law and the prophets (3:21), and is explicitly connected here to the promises given to Abraham and his response of faith.

Practical Case Study: Paul draws from the life of Abraham to demonstrate that God’s plan has always been based on grace through faith. This case study explicitly connects the gospel with God’s original promise to bless all the nations through Abraham.

Pay close attention to how Paul introduces Abraham: “our ancestor according to the flesh.” In Romans 7–8, Paul develops a flesh/spirit dichotomy, but here flesh stands in opposition to belief. Abraham is the ancestral father, the patriarch from whom Jews and many other peoples trace their lineage. But not all of the descendants of Abraham’s flesh are considered part of the covenantal community, and Paul asserts in 4:11 that belief matters more than lineage. Introducing Abraham here as the ancestor “according to the flesh” sets the stage for this.

The big idea for this section is Abraham’s discovery regarding faith and righteousness. The remainder of material strengthens Paul’s argument and fills in important background information before he concludes with the question in 4:9. In verse 2 he introduces a hypothetical situation that considers the implications if Abraham had actually been justified by works instead of by faith.

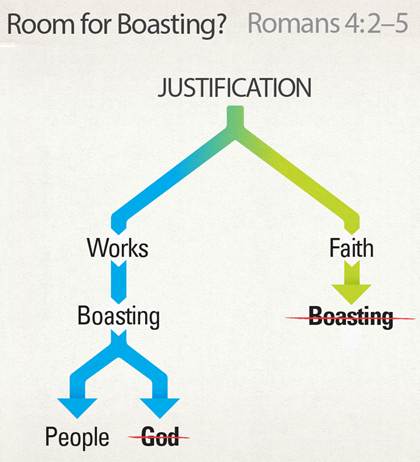

Room for Boasting? Justification by faith versus works leads to different outcomes. Justification by works might be something to boast about, but not before God. In contrast, justification by faith leaves no room for boasting, either before men or God.

If justification is really by faith in what God has done, there is absolutely no room for boasting in what we have done. But if justification is based on works, then people may boast in self-righteous pride, even though there is no legitimacy for boasting before God, or before people for that matter. Paul is driving home the point that there is no room for Christians to boast—other than in our need for and unworthiness of God’s gracious gift. He wants to reveal boasting for what it is: an illegitimate arrogance that fundamentally contradicts the gospel message of justification by grace through faith. In 4:3 Paul offers support for his assertion by quoting Genesis 15:6. Since it was Abraham’s faith that led to him being credited with righteousness, there is no room for boasting.

The next point in Paul’s argument supports the big idea introduced in 4:1. He makes his first point in 4:2–3, and in verse 4 he introduces the next one, consisting of two parts. The first one contrasts how we regard the credit someone has worked for versus credit granted without work. Paul likens it to the difference between a paycheck and a gift.

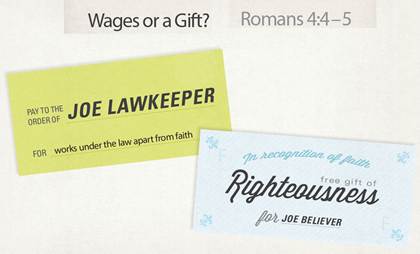

Wages or a Gift? There is an important difference between receiving something as a gift rather than as wages. Whereas wages are owed for work performed, there is no obligation associated with a gift. It is freely given and freely received.

When you work, you expect to get paid. In fact, James 5:4 condemns those who do not pay their workers. But there is no grace involved in payment—it is an ethical obligation. And consider the corollary: If you get paid for work you claim to have done but never did, you have committed fraud. Paul’s point is that work and wages go hand in hand; if you have one without the other, it is probably illegal. So if works are somehow involved in justification, then there is no room for grace.

Paul’s assertion becomes more apparent when we consider the opposite side of the coin: being given something that we did nothing to earn. If we did no work, we have no grounds to boast (3:27; 4:2). The defining characteristic of a gift is that it is free, not based on anything we have done. Think back to the relationship between work and wages. Obligation distinguishes wages from gifts.

The key takeaway here is that grace negates any need for us to work for our justification—it can only be construed as a faith-based gift. As soon as we add works into the equation, it fundamentally changes the proposition. Note Paul’s use of an alias expression for God in 4:5 to reinforce his point. An overt mention of God might prompt us to think that He is not gracious to unworthy folks like us. But by calling Him “the one who justifies the ungodly,” Paul evokes a grace-based image that all but excludes the notion that works could be involved. The idea is that God justifies us versus us doing something to be justified.

Paul creates one big subordinate clause in 4:6–8 in which he bolsters his claim from verse 5. His sentiment about the righteousness we receive is reflected in David’s proclamations, quoted from Psalm 32:1–2. The focus here is not on forgiveness being a gift, but on the blessing that comes from receiving this unmerited favor.

We might think that Paul’s argument in 4:1–8 would end any debate about the nature of justification by faith and its relationship to works. But Paul goes on to tackle several other potential counter-arguments to demonstrate the free and unmerited nature of the justification God offers through Jesus’ death and resurrection.