Steven

E. Runge, High Definition Commentary: Romans

(Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2014), 81-89

Romans 4:9–25

Many English Bibles include a paragraph break at 4:9 but do not have a new topic heading until verse 13. The Greek word introducing verse 9 suggests the sentence acts as a summary proposition drawn from the preceding argument. Again Paul uses a rhetorical question and answer to introduce a big idea—the role Abraham’s circumcision played in him being credited with righteousness. If Abraham’s faith brought about his justification, then what role does circumcision play? Abraham’s experience also has implications for those who come after him—if circumcision qualified Abraham for his blessing of righteousness, then the same should hold true for us.

Paul tackles this issue by looking at the chronological order of events. Which came first, circumcision or being declared righteous? After clarifying the timeline, Paul draws some conclusions.

Timeline of Events: Timing is everything, especially for those claiming that Abraham’s circumcision played a role in God declaring him righteous. Paul recounts the timeline of events to highlight that Abraham was declared righteous before receiving the sign of circumcision, not after.

Paul asks a question in verse 9 without providing an immediate answer. He asks several more questions in verse 10. Remember that the language from the Psalms quotation uses “blessing” instead of “gift” to characterize righteousness. Notice also that Paul’s question concerns the exclusivity of the blessing, whether it is only for the circumcised or for everyone (i.e., the uncircumcised as well). He gives a partial answer at the end of verse 9, where he repeats the Genesis quotation he cited in 4:3. He cuts to the chase in verse 10, asking whether Abraham was circumcised or uncircumcised at the time he was credited with righteousness. In the second half of the verse, he answers with both positive and negative statements to reinforce his point.

What role does Abraham’s circumcision play, since it did not factor into his obtaining righteousness? Paul provides the answer in verse 11: Circumcision never figures into justification. Rather it is a sign, a seal of what has already been obtained by faith. Why does this matter? It opens the door for Abraham to be considered the father of all who believe, circumcised or not.

Paul describes one part of this “all who believe” at the end of verse 11—the ones who believe “through uncircumcision.” The Greek wording makes this sound more like a path than a state of being, as in verse 10. Paul characterizes uncircumcision as if it were part of the means by which some obtained their righteousness. Paul words it just as he did the other means he has mentioned: “through the righteousness of faith” at the end 4:13 or nullifying the law “through faith” in 3:31. This first group believed through their uncircumcision. Stating it in this way, Paul heads off the possibility of misconstruing his claim. There is nothing deficient or lacking in how they obtained their justification.

In contrast, the second group is introduced through Paul’s statement that Abraham is the “father of the circumcised.” He goes on to elaborate that Abraham is father not only of the circumcised (in state, not by means), but also of those who follow in the footsteps: “the uncircumcised faith” of our father Abraham. It is a specific kind of faith—not their circumcision—that defines them. It is the faith that Abraham had while uncircumcised.

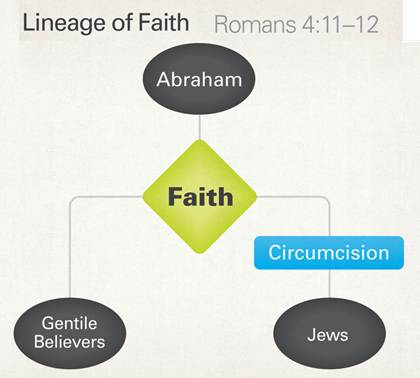

Lineage of Faith: Paul makes the bold claim that the heirs of Abraham’s promise are those who respond in faith. Therefore, both Jewish and Gentile believers are counted as heirs. Circumcision (or lack of it) does not affect this status.

Talk about a slap in the face—Paul has reversed the expected descriptions for these groups. Abraham has always been thought of as the father of the circumcised. His faith might have been credited as righteousness, but circumcision has traditionally been his link to his descendants. The uncircumcised Gentiles are late arrivals who have been grafted into the family tree after the fact, as in 11:17–20, where native branches were broken off to make room for the wild olive branches to be included. Here, though, Paul characterizes the situation as if circumcised believers are following in the footsteps of the uncircumcised believers, of whom Abraham is the father. Paul does not use “means” language of any kind in his description of the circumcised. He describes circumcision as a state that by itself is not sufficient to qualify people as descendants. It is their faith that qualifies them, nothing else—an uncircumcised faith, the kind Abraham had when it was credited to him as righteousness.

Wow! Despite the clear and unchanged chronology of events, Paul’s audience likely treated circumcision as part of justification. This belief was the motivation for Jewish believers who wanted Gentile believers to adopt Jewish practices, as in Acts 15:1. Over time, cultural mores can take on greater significance in practice, even if we understand theologically that they are secondary. We must keep in mind that we are not immune to making our own additions today.

Although 4:13 begins a new paragraph in most Bibles, it is clearly marked in Greek as supporting information for verses 10–12. Paul adds information to his argument, but it is not his next new point. The rest of chapter 4 offers support for his assertion that Abraham was circumcised after his faith was credited as righteousness, and that circumcision was a sign or seal of this righteousness.

Paul uses positive and negative statements to say the same thing twice in 4:13. Either would have been sufficient, but stating in verse 13 that the promises to Abraham were not given through the law sets the stage for the supporting statement in verse 14: If the promises came about through the law, then faith is void and the promises null.

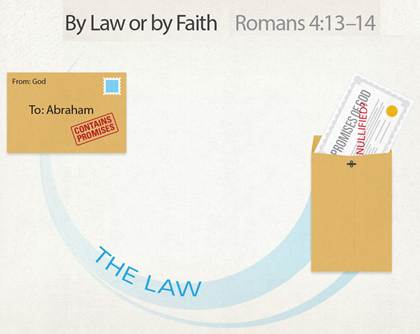

By Law or by Faith: How is it that Abraham received the promises of God? Was it through the law or by faith? If it was through the law, then the promises are nullified.

Paul’s next support statement, in verse 15, describes what the law does produce—wrath stemming from the judgment of sin. Note that this only happens where the law exists. No law means no sin. The context of Paul’s argument here is similar to that of 2:12, where Paul suggests that the Gentiles respond to a different sort of law, one which is written on their hearts. Here he simply considers what the law produces, not the potential response to it. The differing arguments lead to differing conclusions all stemming from a very similar starting point.

Recall that in Romans 3, Paul asked whether some Jews’ unbelief nullified God’s promise. Here he considers how these promises came about in the first place. If some received the promises based on keeping the law, then according to Paul these promises are nullified.

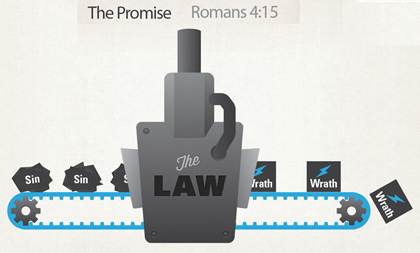

The Promise: The law promotes knowledge of sin, and thus was never intended to produce anything besides wrath.

Why? The law produces nothing but wrath, as it was designed to do. It reveals God’s character to a sinful world in order to convict people of their sin.

In 4:16 Paul draws a logical conclusion from his statements in verses 14–15, affirming his initial claim in verse 13 about the promise being based on faith rather than the law or works. He places the two beneficiaries in opposite order from that of 4:11–12, but with the same “not only … but also” connection. Instead of “circumcised” versus “uncircumcised,” he describes them as “those of the law” versus “those of the faith of Abraham.” Although it is clear which is which, Paul manipulates the terminology to thematically characterize each group for the purpose of his present argument. This is not just stylistic variation. Despite the significance Paul has attributed to faith, he casts Jews as if they are not in this faith-based group. We might have expected “those of the law” versus “those not of the law,” or “those with the faith of Abraham” versus “those without the faith of Abraham.” Instead we find a mixed metaphor. After all, not every Gentile possesses Abraham’s faith—only those who believe. Nevertheless, Paul paints with broad strokes to accomplish the rhetorical task at hand.

The end of the chapter focuses on the impossibility of the fulfillment of the promises made to Abraham: It’s not just that he had many descendants, but that he and Sarah began their family well after the expected childbearing years. Paul includes extra thematic information at the end of verse 17 that re-characterizes God as the one who makes the dead live and calls things into being that don’t exist. This image of God sets the stage for the exposition Paul offers next.

He also recasts Abraham as one who hoped and believed that God could fulfill what He had promised (4:18). By doing this, Paul gives us a glimpse, in verse 19, into how Abraham likely saw himself—as good as dead based on his advanced age, besides the fact that Sarah was barren.

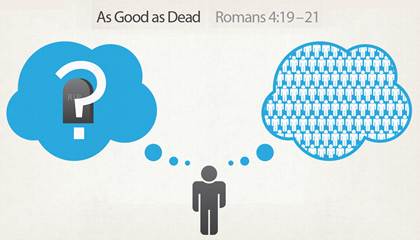

As Good as Dead: Abraham’s decision to trust God’s promises did not come at a time when he had any hope of obtaining an heir naturally. He and Sarah were far beyond childbearing age, requiring a supernatural solution in order for the promise of heirs to be fulfilled.

So it’s not just that Abraham received a promise and was willing to believe. He received an unbelievable promise, one that sounded impossible without some kind of divine intervention. This impossibility explains why Sarah offered her handmaid as a wife (see Genesis 16) since she couldn’t begin to imagine that she could have children. In 4:20–21 Paul describes Abraham as unwavering and fully convinced in his belief. In 4:22 the Greek marks that Paul is drawing out his summary conclusion: Abraham shows complete and unwavering faith when faced with logical impossibilities, and this faith is credited to him as righteousness. This is the benchmark Paul puts forward—this is the kind of faith that saves.

Paul closes with a reminder that his quoting of this significant verse from Genesis 15 was not an “attaboy” for Abraham, who is long since dead and buried. He quotes it for our belief, throwing down a gauntlet that would challenge everyone. He challenges the notion that works or outward signs like circumcision have any effect on God’s assessment of our lives. What matters is our unwavering faith in something that makes little sense—believing that God is both willing and able to accomplish what He has promised. And this reliance on faith is not some late development in God’s grand scheme of things—it has always been the sole basis for justification, as Paul’s case study of Abraham’s life makes clear.

With this case study, Paul also provides specific evidence to support his claim that “righteousness by faith” has been attested by the law and the prophets (3:21). By going back to where it all began with God choosing a people for Himself, Paul definitively demonstrates that his message supports and upholds the law and its teachings. Rather than overthrowing or contradicting the law, his quotations provide evidence that faith has always been the means of obtaining God’s gracious gift. The gospel is not a new plan, but fulfilment of what has long been anticipated by faith in things not yet seen.

Summary for Romans 1:18–4:25

Paul’s primary objective in this section is to establish that everyone, Jew and Gentile alike, faces the wrath of God, which has been revealed against impiety and ungodliness (1:18–19). “Everyone” includes pious Jews who believe they are somehow exempted; they, too, are guilty of the very things they preach against (2:1–9). In chapter 3, Paul tackles the issue of whether there is any advantage to being a Jew if everyone is under God’s wrath. His initial positive answer in 3:1 gives way to a more sober answer beginning in 3:9. In 3:21–26 Paul outlines the new righteousness that has been revealed, one that is intended for everyone—not just those who keep the law. Just as God’s wrath levels the field for both Jew and Gentile, so too does this righteousness brought about by Jesus’ death and resurrection. As a result, no one has any basis for boasting, and pride is completely removed since justification is made available only by grace through faith in Christ. Abraham’s experience proves that this has always been God’s plan. Now that he has addressed the question of God’s wrath, Paul resumes the themes of 1:16–17 regarding the practical implications of gospel and its power of salvation to all who believe.