Steven E. Runge, High

Definition Commentary: Romans

(Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2014), 157–164

Romans 9

Romans 9:1–13

Paul has covered a huge amount of material in these first eight chapters. From a rhetorical standpoint, it seems as if he is siding with the Gentiles against the Jews as he makes his various points about the gospel. In Romans 2:17–23, he claims that circumcision and knowledge of the law do not exempt a person from God’s judgment. In fact, boasting in such things while breaking the law blasphemes God’s name. In 2:28 he makes clear that the internal, not the external, is what matters. This leads to the question in 3:1 of whether there is any advantage or value in being a Jew. Paul answers yes, but provides only one reason.

Even so, Paul is not taking sides; he is correcting misconceptions about the gospel. Much of his effort thus far has been focused on Jewish misconceptions of the gospel. Jews are just as much under God’s wrath as the heathens described in Romans 1:18–32. Law-keeping and circumcision do not replace faith as the basis of salvation. Paul presents Abraham’s experience as a test case in 4:1–23, and drives home his point that salvation has always been based on faith, not works of the law.

Understanding the role of faith would not only affect Jewish understanding of salvation, but also their regard for the Gentiles and their salvation. If, indeed, a righteousness from God has been revealed apart from the law, and this righteousness is given through faith, it changes everything—the role of law-keeping for the Jew as well as the burden of law-keeping for Gentile believers. In Romans 3:27, Paul summarizes the consequences of this newly revealed righteousness by faith: No longer is there any room for boasting in the law or one’s covenant status with God. Faith in Christ’s atoning work on the cross is the only basis for salvation.

This sense of Paul taking sides is a natural consequence of his task thus far—dismantling any possible Jewish argument for considering themselves better than the “Gentile sinners” (see Gal 2:15). He wants the self-confident Jews to reconsider that in which they have placed their trust—the law—in light of this righteousness from God that has been revealed through Jesus’ death and resurrection. Paul’s argument would likely have shaken their beliefs to the very core, leading them to question much of what they believed to be true.

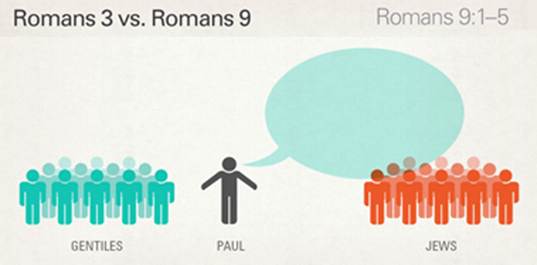

Romans 3 vs. Romans 9: Based on the nature of Paul’s argument thus far, it seems as if he were talking primarily to the Jews, addressing misconceptions about the gospel, law, and the Gentiles. It almost seems like he has been siding with the Gentiles.

If anyone is keeping score, it might seem that Paul has been playing on the Gentile side and that all the points are in their column. But Paul has focused his attention on the Jews, not because he is against them, but because he is not playing favorites. He is pursuing some very specific goals: first, to demonstrate beyond all reasonable doubt that Jews and Gentiles are in the same predicament when it comes to sin, wrath, and judgment; and second, to explain that there is only one plan for reconciliation with God, salvation through faith. Contrary to popular Jewish belief, there is no distinction between Jew and Gentile; both share the same problem and the same solution. As Paul heads deeper into chapter 9, he shifts gears to address some of the remaining implications of this “salvation by faith” gospel.

Romans 3 vs. Romans 9: Paul’s argument thus far has primarily addressed Jewish misconceptions about the gospel. But Paul is neither anti-Jew nor anti-Gentile. He has not taken sides, but he instead stands against misconceptions of the gospel. In the next section, he begins to address Gentile misconceptions about the gospel and its implications for Israel’s status before God. The tables are about to turn.

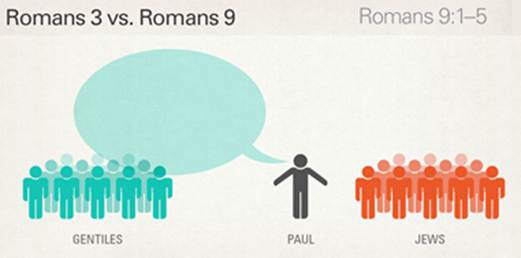

Notice how Paul recharacterizes the Jews as “his brothers and his fellow countrymen according to the flesh who are Israelites.” No longer is he portraying them as potential blasphemers of God’s name (2:24) or rebels whose throats are like open graves (see 3:10–18). Paul uses these impassioned words to express the grief and distress he feels regarding the plight of his people (9:1–2), then he immediately cites the unique privileges they enjoy. Contrast the list in 9:3–5 with the one-item “list” of 3:1 following Paul’s “much in every way” statement. The contrast here is not an oversight by Paul, but an intentional rhetorical strategy.

As he writes each section, Paul has specific motivations and objectives in mind. In Romans 3 he acknowledged advantages to being Jewish, but listing those advantages would have been counterproductive. His purpose was to help his Jewish audience understand that they have the very same need for the gospel as the Gentiles. In Romans 9 Paul prepares to address a problematic issue: God’s faithfulness to His covenant promises. If there is really is no distinction between Jew and Gentile, then what does the Jews’ covenant status with God matter in the big scheme of things?

Romans 3 vs. Romans 9: In response to the rhetorical question about advantages enjoyed by Jews in 3:1, Paul names only one thing. Although he acts as if he will list more, he stops at one. Now in Romans 9, as he is addressing Gentile misconceptions about the gospel, Paul provides the kind of list the Jews expected to hear back in Romans 3. The lists differ according to Paul’s rhetorical goals for each context.

Paul’s lengthy list of advantages in 9:4–5 gives his audience the impression that he could go on indefinitely. But he makes a somber shift in verse 6, one we can anticipate based on his statement in verses 2–3: He grieves and is greatly distressed for his fellow Israelites and would wish himself accursed on their behalf. But why? We must think back to Romans 4.

As Paul described Abraham’s faith-based acquisition of righteousness, he introduced the notion that not all of Abraham’s descendants partake in the righteousness he obtained. Although God’s promise is available to all of Abraham’s descendants, only those who respond in faith actually acquire it—even if they are not his physical descendants (4:13–16). Paul first raised and partially addressed the issue regarding Abraham’s true descendants back in 4:14; he picks it up again here in 9:6.

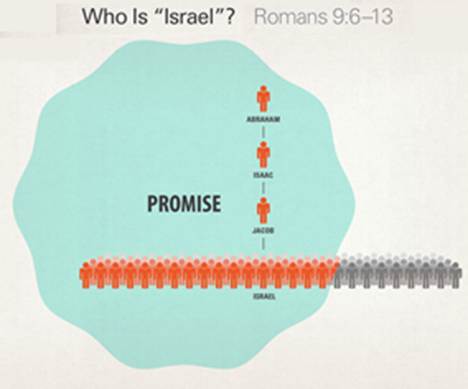

Who Is “Israel”? In Romans 9:6–8 Paul restates this information three ways to clarify how he defines the people of God according to God’s promises to the patriarchs. In the following verses he provides numerous Old Testament quotations to support his assertion that not every physical descendant of Abraham is a member of “Israel,” as reckoned by the promise.

Paul’s claim that Abraham’s real descendants are reckoned by faith and not by lineage has significant implications. It defines the people of God by something other than national lines. Since not all of Israel has believed with the faith of Abraham, in Paul’s view, the nation itself cannot be equated with the people of God. We saw this already in 4:14, where physical lineage was not the determining factor for obtaining righteousness. If it had been, then faith and the promises of God would have been rendered null and void. But those who respond in faith, even though they are not physical descendants, are still counted as Abraham’s heirs according to faith. They have membership in the people of God because of their faith, not circumcision or national lineage.

But there is another side to consider—those who are physical descendants of Abraham but do not respond to the gospel in faith. How should we regard God’s covenant faithfulness to these non-believing descendants? These people are part of Israel, but are they part of the people of God? Have God’s promises somehow failed? Paul asks this question in 9:6 to introduce his main theme for the next three chapters. His answer lies in understanding the important distinction between the nation of Israel and the people of God.

Paul’s initial answer restates the same basic message three ways in verses 6–8 to make sure that no one misses his point.

• Romans 9:6b: “Israel” ≠ all Israel

• Romans 9:7: Abraham’s children ≠ all Abraham’s descendants (e.g., Isaac not Ishmael)

• Romans 9:8: children of God ≠ children of the flesh; rather, children of God = children of the promise

The Greek grammar here is difficult to render clearly in English. Each of the statements presupposes the existence of an Israel, descendants of Abraham, and children of God. The question is who, exactly, composes each group? Paul provides an answer with each statement—and these claims are not what we might think. Adopting and retaining this view of Israel is the key to understanding Paul’s entire argument of Romans 9–11.