Steven

E. Runge, High Definition Commentary: Romans

(Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2014), 165–171

Romans 9:14–29

The question of whether God has failed to honor His promises to Israel serves as the big idea for this section of Romans. Paul tackles it in smaller bits, beginning with defining who Israel is. Instead of answering the question of God’s faithfulness with a yes or no, he reframes the question in 9:6b–8 with the three identifications of Israel—as something other than the genealogical descendants of Abraham. Paul is not talking about God saving the nation of Israel, but His own people who have responded in faith. His contention is this: Our perspective on God’s covenant faithfulness will change if we truly understand “Israel” as God does. In the remainder of 9:9–13, Paul presents attestations of the same principles from the Old Testament. Biblical history consistently demonstrates a winnowing down of the patriarchal line: Isaac was chosen rather than Ishmael, Jacob rather than Esau.

Paul returns to his main argument in verse 14, addressing two implications stemming from the idea of God’s sovereign activity. Is God just, if He chooses some and not others? Consider it this way: If His choice brings about a foreordained result before I can be involved, is that fair and just? Paul answers “No way!” and then supports it by quoting Exodus 33:19 about God’s sovereignty. Paul now has the groundwork to draw out a logical consequence in verse 16. God’s choice is a matter of Him showing us mercy, not a matter of our wants or actions.

We have a tendency to view God from one of two perspectives. In the first, we might see Him as the loving God who cared enough to send His only Son to die for us, with whom we can have a close and intimate relationship. His love for us is indeed unfathomable, and His knowledge of us is incomparable. After all, He specifically created us for His special purposes, which means we are special, right? All of this is true, but it’s our perspective. The corollary—God’s perspective—is that He specifically created us for His special purposes.

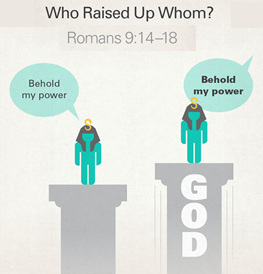

Who Raised Up Whom? God’s plans result from both human agents making decisions and God’s divine prerogative to accomplish His purposes. As creator, He has sovereign authority to do as He wishes. Thus, while Pharaoh made decisions about releasing Israel from slavery, God’s hand was at work, demonstrating His power through Pharaoh.

Paul highlights this point in verse 17 by mentioning the hardening of Pharaoh’s heart during Israel’s exodus from Egypt. We take comfort in God’s love and His plans for us—until His purposes are at odds with ours. God raised up Pharaoh only to harden his heart—in order that His name would be proclaimed in all the earth. He might have used any number of other means to accomplish this outcome, but He sovereignly chose hardening Pharaoh’s heart. God’s divine prerogative is not made in consultation with others. He ordains things in such a way to ensure His plan comes about.

God knew Pharaoh intimately and created him especially for His purposes—just as much as you or me. Still, it seems unfair that God would harden someone to accomplish His purposes; after all, He could just as easily harden me. But this is precisely Paul’s point (see Rom 11:22). God is God and we are not. In His infinite wisdom, His purposes and intentions take precedence over ours; there is no room for discussion.

If we neglect God’s sovereignty to accomplish His purposes, we can think more highly of ourselves than we ought. God loves us and has a plan for our lives, but we do not have control over that plan. We must never forget who is in charge (it’s not us). Paul is driving home the lesson that to have a proper view of God, we must hold these two perspectives in tandem. It is a biblical reality, but not the whole picture.

At the same time, in an elusive and non-contradictory way, we do have a choice in how we respond to God. Paul addresses this issue elsewhere in Romans—when God reveals His wrath against those who have rejected Him (1:18–21), when a person passes judgment on others (2:1–4), when some of Israel rejects the gospel (11:14–15). Paul will not let us overlook the role of human responsibility. Because we are culpable for our actions, God is just in holding us accountable for our sin (6:23), despite the factor of divine sovereignty.

But Paul raises an additional question in 9:19. Most of us tend to have this general notion of cosmic justice in which all of us are repaid according to our own actions. Yet we have no control over countless factors that affect our lives, such as the circumstances into which we are born. But Paul goes well beyond this general kind of sovereign decision to God actively, divinely intervening in someone’s life—directing someone’s will with His own. If God is making decisions that are beyond my control, then why am I accountable for them?

God’s Sovereign Choice: Paul uses the illustration of the pottery questioning the potter’s design decisions to highlight the folly of questioning God’s divine prerogative. Just as the potter has authority over the clay to do as he sees fit, so too does God shape us to be most useful to Him.

This logical question is essentially sidestepped by turning the table on the questioner. Paul poses rhetorical questions in verse 19 and responds with another series in verse 20. These questions form a subsection within 9:14–29. Paul give us another dose of “divine sovereignty”—a reminder that we are not in control. God’s purposes supersede ours (9:21), but there is far more to it.

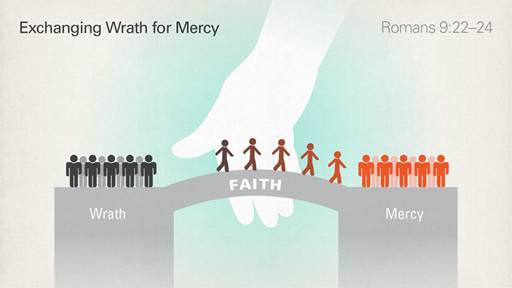

Paul introduces what might sound like a hypothetical scenario in verse 22, but it actually provides a thumbnail view of God’s decision-making. It presupposes that part of God’s creation incurred His wrath. We know from Romans 1–3 that all of us have sinned, leading to God’s wrath against our rebellion. God would have been completely justified in executing judgment against us, but that is not what He chose to do. Instead, He allowed a larger purpose—the desire to make His power known—to supersede a demonstration of His wrath. Revealing His power demanded a higher degree of patience with the “vessels of wrath prepared for destruction” than just wiping us out.

This delayed judgment on our wrath-deserving sin was already mentioned in Romans 3:25–26, where, in His forbearance, God passed over our previously committed sins. Recall that the passing over is not a sweeping under the rug—otherwise God could not be both just and justifier (3:26). Paul mentions both of these themes in 9:22 as well, demonstrating God’s wrath and making known His power. God’s wrath must still be addressed, but He has delayed it out of a desire to make His power known. Note that this is the very same desire that led Him to harden Pharaoh’s heart (9:17).

So what was God’s motive for patiently enduring vessels of wrath like us, vessels prepared beforehand for destruction? Paul says it was something more than just His desire to demonstrate His power. In 9:23, Paul says that His power is manifested by making known the riches of His glory to these vessels—and note the change in how the vessels are characterized. No longer are they full of wrath and destined for destruction; now they are vessels of mercy He had prepared beforehand for His glory. This idea of being “prepared beforehand” links back to God’s larger plan and the notion of election. And lest we mistakenly think that Paul has only Jewish believers in mind, he clarifies in 9:24 that God’s plan also includes Gentiles. Once again we see that we cannot equate the nation of Israel with the people of God. For Paul, the people of God are determined by their response in faith, not their lineage.

Exchanging Wrath for Mercy: Immediately after affirming God’s divine right to do as He sees fit with humanity, Paul introduces a hypothetical situation that describes what God actually did. Rather than leaving us to face destruction, He patiently bore with our sin and provided His own righteousness to all who would believe.

Knowing the inclusion of the Gentiles is unexpected, Paul counters with quotations from Hosea, where those who were not called God’s people and were not loved by Him experience a reversal on both counts. The original context of Hosea focused on restoration for those who had walked away. Here in Romans, Paul adds another layer of restoration—the inclusion of Gentile believers, those outside of Israel, among the children of the living God (9:26). Paul affirms once again that God’s people cannot be identified by nationality, but only by a response of faith.

In 9:27 Paul narrows the scope back down to Israel. He shifts analogies from the restoration of those who have fallen away to the concept of a preserved remnant within Israel. Nevertheless, he promotes the notion of an intentionally selected group from within a larger group. God could have chosen to preserve all, to restore all, but He chooses to restore only the remnant.

These quotations from Hosea reinforce Paul’s initial premise of this chapter—that real “Israel” and the ethnic Israel are not identical. Rather, the real Israel—the true people of God—consists of a believing subgroup of the nation in addition to the believing Gentiles. Paul used this same kind of delineation in Romans 4:11–12 to describe Abraham’s true descendants. Paul repeats these analogies to explain that it was never God’s intention for His chosen and redeemed people to include every descendent of Abraham.

The apostle’s main point is to rebut the concept that Israel rejected the gospel because God’s promises to them had somehow failed. He demonstrates that this line of thinking represents a fundamental misunderstanding of God’s plan of salvation, which was never exclusively for Israel, whether in whole or in part. Rather, the nation of Israel was the means by which God’s blessings were to extend beyond them to all nations. God’s plan of salvation includes all of creation, not just His chosen people (see Rom 8:18–23). The inclusiveness of the gospel has huge implications—there is no room for claiming that Jewish law-keeping is a prerequisite for belief in the Messiah.

The second, likely shocking point of this section is contained in the first. Paul has just reminded his Jewish audience that the people of God include believing Gentiles. Here he makes explicit that the salvation of Israel never entailed the entire nation. The many Old Testament references to the preservation of a remnant align with Paul’s description of God’s purposes according to election (9:11). Not every physical descendant of Abraham is elect; God’s purposes dictate who is hardened and who is shown mercy (9:16). Paul makes no apologies here. God is the one who created us for His own purposes and designs, and we owe our entire existence to Him, period (9:21). God’s unique position of Creator brings with it a divine prerogative to accomplish His purposes with His creation. As His creation, our role is to trust, not to like or dislike His plans.

But lest we conclude God is whimsical or manipulative, Paul reframes his argument again: God’s offer of salvation requires His patient endurance of our sin and our well-deserved punishment in order to demonstrate His wrath and power (9:22). This plan enables Him make known the riches of His glory to us—the vessels He created beforehand. The course of human history—from the first sin, our rejection of God, living in slavery to sin—are all part of His larger plan, not only for Israel, but for all people of the world (9:25–29).